Meet the hiker bringing off-roading wheelchairs to LA

Published in Lifestyles

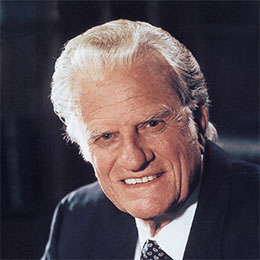

LOS ANGELES — It’s a crisp, clear Southern California day, and I’m at Frank G. Bonelli Regional Park with Austin Nicassio. He’s ripping up a steep dirt trail covered in rocks and roots in what looks, at first blush, like a miniature bulldozer. Until this moment, I wouldn’t have considered this particular hike to be accessible to those in wheelchairs, but with Nicassio’s all-terrain rig, it’s a possibility.

Inspired by organizations across the U.S. that are advocating for public access to trails for those with disablities, Nicassio launched the nonprofit Accessible Off-Road in October. His plan is to expand free access to off-road wheelchairs for Los Angeles County residents with mobility disabilities to use at popular trails across the region. The chair he’s using, he said, is the first of many.

“I was thinking so small-minded — I was like, ‘One or two chairs is going to be so life-changing for thousands of people,’” Nicassio said. “I’m talking to all these superintendents, I’m talking to rangers, everyone is excited, they started crafting an agreement ... and [officials at California State Parks] say, ‘This is great, I think we’re going to gauge interest across our 280 park units.’”

That’s the dream, but it would require Nicassio’s organization to raise millions of dollars in funds.

To start, Accessible Off-Road is fundraising for $45,000 to launch a pilot program with two chairs at two parks, and then use lessons learned through the pilot program to add more chairs to other parks across Southern California. He’s talking with officials at L.A. County Parks and Recreation, California State Parks and the National Park Service (although the current funding crisis has delayed those conversations).

“At [Bonelli Park] or Griffith Park or Crystal Cove, these destinations with hundreds of thousands of visitors per year, one chair can create unforgettable memories for a person every single day, and the cost-benefit to that to me is so obvious,” Nicassio said. “That’s 365 individuals [a day] who’ve lost access like myself or have never had access to something like this ... [making] unforgettable days for yourself and your family.”

Nicassio, an astronautical engineer at Boeing, was not born with a mobility disability. In 2022, he had a mild case of COVID-19. That’s when everything changed. He developed muscle weakness, fatigue, body soreness and brain fog. He was also sleeping more and more, eventually up to 20 hours a day. He had to stop working and was bedbound for a year.

He was diagnosed with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, which affects his blood flow as his body struggles to maintain steady blood pressure, especially between sitting and standing. He also developed chronic fatigue syndrome, also known as myalgic encephalomyelitis.

He felt trapped in his body and his mind, unable to blow off steam like he used to through mountain biking, running or hiking.

“For the first 28 years of my life, I was able-bodied, never thought twice about it, took it for granted,” he said.

Once he was well enough, Nicassio bought an electric trike and started mountain biking with his family and friends. But in the trike, he was in a static position, and it would trigger the symptoms of his blood flow disorder, causing him to feel exhausted and ill.

Nicassio started researching off-road mobility devices and discovered a legacy of nonprofits providing over 100 off-road wheelchairs free to rent across the U.S. at public spaces. There wasn’t an organization like that in Southern California.

“Being able to spend $1,000 on an electric trike is not in reach for a lot of people when you’re trying to cover your basics — your medications, your appointments,” he said.

The off-road wheelchairs are even more cost-prohibitive and rarely, if ever, covered by health insurance carriers. The chairs are typically about $20,000, although Nicassio has struck a deal with the larger manufacturers to buy them at a discount through his nonprofit.

Nicassio can walk short distances, like around his house, to the bathroom or to take a shower, but extended standing and walking is challenging, and can even be dangerous given he could pass out. The first time he took the off-road chair out, he felt like he’d regained a freedom he didn’t think would return.

Similar to how a tank moves, the off-road chairs use two rubber tracks to guide the user along. It provides substantial traction over a wheelchair. The controls are similar to that of an electric wheelchair, with settings that allow the user to move their center of gravity as they navigate over rocks and branches and up and down steep hills.

The chairs that Nicassio’s group will buy can tackle grades up to 25% and go through up to 8 inches of water. They do well on sand and beaches too.

Accessible Off-Road will develop a checkout system with parks. Initially, it’ll be a fairly simple process where users provide a driver’s license, sign a waiver and receive a quick orientation of the chair, especially if they aren’t using wheelchairs often in their day-to-day lives. Eventually, Nicassio hopes to develop a mobile and web checkout system.

The organization will identify the best trails for users to hike in the chair to ensure folks remain safe. And users will be required to hike with a friend or family member in case of emergency. The chair has a lithium battery and can go an average of 14 miles.

The chairs come with a control panel on the back, so if someone doesn’t have use of their hands, their friend or family member could control the chair as they take the path.

As an outdoors reporter, I am often asked what the difference between walking and hiking is. I often explain that hiking requires a level of thinking and technicality that walking does not. I posed the same question to Nicassio.

“It starts with how I define going for a walk with my dog. Before, it really had to mean walking with legs, standing up on your own two feet. But nowadays, I have another chair that’s not 400 pounds, doesn’t need a sprinter van to transport, I break that puppy out, and we go for our walks, and it feels like a walk. I get all the benefits of a walk. My dog gets exercise. I feel like that chair becomes an extension of me, and it’s walking. So, if that’s walking, this is hiking.”

©2025 Los Angeles Times. Visit at latimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments